Fake News, Advertising, and Programmatic Buying

Fake News, Advertising, and Programmatic Buying

In December, the New York Times ran an article about fake news and advertising networks, "Advertising’s Moral Struggle: Is Online Reach Worth the Hurt?" It's a story about the challenges of algorithms picking ad placements in networks based on following prospects wherever they might roam online. What caught my attention is the comment that this:

"has inserted a new ethical cost into the automated advertising equation, which promises companies large, desired audiences at low prices with little need for human intervention"

After I read that, I thought, "Has it? Has it inserted a new ethical cost?"

Easily abused

From my first foray into the world of sales and marketing to the present, the struggle with ethics has been there. Whether it's the use of "tie-down" closes that take advantage of our human tendency to defend previously stated positions or our tendency to latch on to anything sexy or funny, the profession tends to justify the ends over the means. That's a recipe for moral quandary.

The question is, now that you know about it, what are you going to do about it?

Now you know

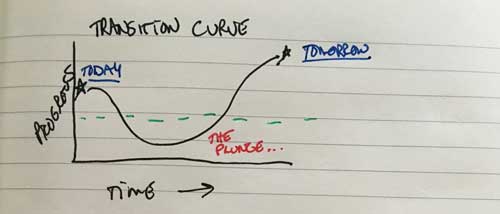

Let me give you a story. Back when I sold tropical shirts, my first objective was simply to source the shirts. An admittedly low hurdle, but real. I use this graphic when illustrating the movement from unconscious incompetence to conscious competence. I call it the transition curve.

Today represents a state of not knowing what you don't know. The plunge is new knowledge and grappling with it, adding context and layering meaning. Tomorrow represents conscious competence.

When first selling shirts, I didn't know what I didn't know. Then I plunged into conscious incompetence as I learned just how complex sourcing a shirt was. Who could know about the perfect yolk size, how materials held up over time, or the infinite varieties of fabric in the world? You learn. Over time you know what to avoid and what to ask for. I started to feel pretty good about things.

Then I attended a seminar put on by a fabric company and their client, Patagonia. They were just starting on efforts to trace materials all the way through the supply chain, to the source. Not just asking "where does this fabric come from?" but asking "And where did they get that? And where did they get those dyes? And who handled it then?" It was alternately exhausting and exciting to hear about, even if I didn't have the resources to do what they were doing.

Much like this advertising conundrum that has come to our attention.

New information, new direction

Next to me at that seminar was a small wholesaler of bamboo clothing. I had just asked to test samples of their bamboo shirting. As the Patagonia guy and his supplier told their story, I could see the wholesalers shifting in their seats. Both of them were dreadlocked young idealists and they were sinking everything into their bamboo venture. Finally one of them couldn't stand it any longer and asked, "What about sustainable bamboo fabric?"

The Patagonia guy paused and said that they used to offer bamboo fabrics until they learned details about the process that takes rigid bamboo to pulp for making fabric. He said something along the lines of, in the end, we found out that they needed stronger, harsher chemicals to break down the bamboo than they did the cedar rayon fabric that they had been using. So, even though the process of making rayon was harsh, they went back to rayon because it was less damaging to the environment.

My dreadlocked friend had just been presented with new information and had a choice to make. He didn't have the resources of a Patagonia to fund his own detective work, so he could take their information - which would kill his pitch - or ignore it. He was just starting to get traction in his business, but what if his company was built on a lie?

Finding your ads on fake news sites is similar to that bamboo guy finding out his pitch was wrong. Impressions count, clicks count, and conversions count in online advertising. How much does the advertiser care about where that conversion comes from? Especially if it's a small advertiser, running re-targeting ads on a network where finding ad placements is manual work that takes time? What is their responsibility or the responsibility of their agency? After all, those views, clicks, and conversions are funding those fake news publishers, rewarding their behavior.

Don't just sit there

When I first discovered ads being run on questionable sites, I did the same thing I did when I learned the bamboo story. I dug in to learn more. When I found ads on unexpected sites, I went to my clients. Did my client mind ads being shown on a porn site? Did it matter if it were a retargeting ad versus a first run prospecting ad? When I wanted to know more about the fabric in my shirts, I asked if the supplier could share their knowledge with me? Did my suppliers have an opinion or have control of the sourcing?

What I tried to avoid, and I suggest you try to avoid, is acting from a place of conscious incompetence. When new information comes into our world, that's where we are tossed. We go from blissful ignorance, rapidly plunging into "oh man, what else don't I know?"

Fight through it. Dig in. Ask your vendors to dig in. Get more information and get back up to conscious competence. Knowledge isn't a bad thing. Ignoring it is.

Good stuff.